How Language Works

2 Word Meaning

One point all linguists and most other language scientists probably agree on is the centrality of words to language. All aspects of language seem to be tied in some way or other to words. In this chapter, we'll start off imagining a world with no language at all and see what is gained by adding just this one basic feature of human language. Words have two aspects, their forms and their meanings, and in this chapter we'll only look seriously at meaning (though we will think a bit about what sort of relationship there is between form and meaning). Actually we'll only be considering words in one category, those words that refer to things in the world. How people use words to refer is just one aspect of the question of what it means to mean, which turns out to be an enormously complicated topic, one where linguists and other cognitive scientists still have a long way to go. In a way the book is starting off with the hardest topic of all. But the idea of meaning is at the heart of what language is, so we can't really put it off. Even just scratching the surface of this topic, as I'll do in this chapter, will lead us to look at notions that seem to be beyond language: how people categorize objects in the world and how people use one kind of situation to help them understand another kind of situation. But to say anything at all about the meanings of words seems to require an account of where those meanings come from and what good they are for us.

2.1 |

Reference and proper nouns |

A world before language

Imagine a tribe of people much like us. You can think of them as our hominid ancestors, or if you prefer, as a race of aliens on another planet; for our purposes, it doesn't really matter since we will only be using them to help us understand what language does. Like us, they live in a world full of regularity. There are objects around them with characteristic properties: rocks that tend to be hard but to break when they are hit hard enough; plants that tend to be soft and have parts that can be pulled off and sometimes eaten; animals that move and can be dangerous. (We'll let our people be vegetarians.) The world is also regular in terms of what happens: the regular appearance of celestial bodies and seasons; the inevitability of rain following certain kinds of clouds; the way certain animals run away and others attack when they are confronted; the way other members of the tribe respond to friendliness, flirtation, rejection, and aggression.

To survive in their world, these people, like us, have evolved nervous systems that allow them to find these regularities in their world. They can sense the basic features of the world: colors, textures, edges, movements, sounds, tastes, smells, consistencies, hardnesses. Like us, they are also expert learners. This allows them, together with their basic sensory abilities, to discover the regularity in their world. Learning is important for our people because it allows them to survive in very different environments; no matter where they happen to end up — the desert, the mountains, the forest, the plains, the coast — they can figure out what their world is like. Finding the regularity is important in turn because it allows them to learn what kind of behavior is appropriate. If you can identify the edible plants and the animals you need to run away from, you can survive. Even if you can't identify the edible plants and the threatening animals, you may still be able to survive by getting help from others in your tribe. But to get help from others, you have to have figured out what kinds of behaviors lead them to cooperate with you and what kinds lead them to reject or even attack you. If you can't recognize aggression in the face and body of a much stronger member of your tribe, you won't survive.

These people are like us in a number of ways. But they differ from us in one very important way. They do not have language, at least language as we know it. Throughout this book, we will be giving them language, a little at a time, at each step asking what advantages and complexities the new features bring. For now we will refer to them as "Prelings", to emphasize that they are pre-linguistic; they don't have language yet.

While our tribe of Prelings is purely speculative, you are already familiar with a real group of pre-linguistic humans. All people at birth are pre-linguistic in that they do not yet know a language. We can also learn a lot about language by taking the perspective of these real pre-linguistic beings, and we will do this in the book sometimes too.

Objects and individuals

Consider the things in the world that we refer to using the following words:

- box, bird, road, hand

- milk, dirt, air

How is the first group different from the second?

One of the things that both our imaginary Prelings and our real pre-linguistic infant notice right away about their world is that it contains objects, entities with clear boundaries around them that have a number of stable properties. For example, consider an apple, one of the things that both our Prelings and our infant happen to encounter. While some things about an apple can change quickly, its position, for example, others are relatively stable: its color, shape, size, smell, and consistency, for example. The same could be said of a cave, a cat, a bush, or a person (or another Preling). (Note that we are using the word object in a way that differs from the usual, non-technical use of the word in that it can refer to living things, including people, as well as inanimate things such as rocks and plants. This will happen often in the book: the use of a word that you are already familiar with in an unfamiliar, somewhat different sense.)

But not everything in the environment is an object. The water in some portion of a river is not an object because it has no obvious boundaries. And the situation in which a lizard is resting on top of a rock is even less like an object because it is not stable; the lizard may run away at any minute. What about a river or a mountain? We can view a river as an object if we allow a boundary to be the border separating two different kinds of material, soil and water in this case And we can view a mountain as an object if we allow a boundary to be clear on some sides (where the top and sides of the mountain are separated from the air) but not so clear on others (where the mountain is separated from the plain around it). These examples are important because they illustrate a common theme: whenever we attempt to divide up the things in the world in a particular way, for example, into objects vs. non-objects, we will find good examples — an apple is a good example of an object; some water is a good example of a non-object — and others, such as lakes, that need to be stretched to fit into one group or the other.

Prelings and babies are not only good at finding objects; they are good at distinguishing particular objects from one another. A baby learns early on to distinguish its parents from other people. Prelings need to be able to distinguish members of their tribe from one another — their mate, their children, the tribe chief — in order to know how to behave. And they need to be able to distinguish particular bushes and particular hills and bends in the river from each other so that they can know where they are when they are out searching for food. We will refer to particular objects as individuals. Later we'll use this word for particular instances of things other than objects.

Proper nouns

One function of words is to "point" at things. But what advantages do words have over pointing with our fingers?

Our pre-linguistic Prelings are social creatures. They survive by sharing the food they find, by helping each other take care of their young, and by protecting each other from predators. But they are limited in how much they can cooperate because the few signals they have communicate only vague meanings such 'danger!' and 'I am angry' and 'I want to mate.' They can also point to individual objects in order to draw the attention of other members of the tribe to them. But when an individual object is out of sight, pointing won't work.

Consider what the advantages would be of being able to "point" to something out of sight. If one member of the tribe was in danger, another member could let the others know about this by "pointing" to the one in danger. Of course the pointing alone wouldn't convey the danger; the others would have to infer this from the urgency of the pointer's actions. Or the Preling could "point" to a familiar, but out-of-sight, landmark in the tribe's environment, alerting the others that something important had turned up there, such as a previously unknown source of food.

Language offers several ways of "pointing" with words. One simple way is with words which have only this pointing function, words like this and that. We'll learn more about these kinds of words later. For now, note that they have the disadvantage that they say little about what object is being pointed to and in fact have to be used together with other language to make any sense: pick that up, this is my sister.

A more precise alternative is provided by names. They allow us to point to individuals even when they are not there. Nearly all human languages have a category of words we'll call proper nouns that function as names. English examples include Mommy, George, Fluffy, Indiana. In many languages the category of proper names is distinguished formally from other expressions in certain ways. In English, for example, we don't normally precede proper nouns with the word the, unless more than one individual has the name and we are trying to make it clear which one we are talking about. That is, we do not say please give this to the Clark (whereas we can say please give this to the coach). This will be a familiar theme in the book: a particular notion or function of language (for example, naming) may be represented by a type of word or linguistic pattern which is distinguished formally from other words or patterns (for example, proper nouns). This is just another example of our Main Theme, that language is about the relation between meaning/function and form. (Note that proper nouns are not the only possible names in English; we also have expressions like the White House and the Grand Canyon. We'll look at these kinds of names later.)

Reference

The pointing function that names perform is called reference. Most of the time I'll be using this word (somewhat loosely) both for what Speakers do with words and what the words themselves "do". The individual that is referred to is called the referent. I will have a lot more to say about reference, especially in the chapter on Composition. For now, we can think of reference in the following way.

- The Speaker has an individual in mind and wants the Hearer to have that same individual in mind.

- The Speaker produces the name.

- The Hearer recognizes the name, and it activates the representation of the individual in the Hearer's short-term or long-term memory.

Reference by itself can never make the Speaker's complete intention clear, that is, why the Speaker would want to call the Hearer's attention to the referent in the first place. Reference is only one aspect of human language, and Speakers have access to more than just names. But even with the help of a full-blown modern human language, Speakers can never directly transfer what's in their mind to the minds of Hearers. There's always some guesswork involved in interpreting language; this is a topic we'll return to when we discuss how combinations of words are interpreted. In other words, what our Prelings would have to do in understanding their primitive "language", consisting only of proper nouns, is only really different in degree from what we have to do all the time.

Knowing and using names

If there are only a small number of interesting things to be named, it might be efficient to have the list of names built into the Prelings so they wouldn't have to figure them out in every new generation. For this solution to work for real animals, however, evolution would somehow have to settle on it; that is, the knowledge (or whatever) that is required would have to be genetic in the end. And for this to happen, members of the species that are genetically predisposed to produce particular sounds (or gestures) and respond appropriately to them would have to have an advantage over those that aren't. The problem with this possibility is that the knowledge required to produce and understand names is quite complex, and it is very difficult to imagine how anybody could have ended up with a genetic predisposition to have this knowledge.

Let's consider what it would take for a Preling to know a particular name. First, it has to be able to both recognize and produce the form for the name, a sound like "Clark" or some unique gesture that refers to Clark. This alone is not at all trivial, but we'll wait until the next chapter to worry about why. For now, let's just assume that there is some sort of representation for the form of the word in the Preling's brain.

The Preling would also have to be able to recognize the referent of the name, the person, village, or mountain that is referred to. In a sense, then, it has to "know" the referent. But what is "know" exactly? Let's consider two possibilities. First, there is a single "place" in the Preling's long-term memory for the referent, a place that somehow gets activated when the Preling sees, thinks about, or (if it knows the word) hears about the referent. This place brings together all of the various features of the referent, each with its own place in memory, as well as other places in memory that are associated with particular responses the Preling makes when it encounters the referent. This is what I'll call a localized representation. Another possibility is a distributed representation of the referent. Instead of appearing in one place in memory, there are only the separate places for all of the different features and responses that are associated with the referent. These are connected with one another in a large network of relationships in such a way that when enough of them are activated, the whole set of places that are associated with the referent become active. In the distributed view, there is no single place in memory that gets activated when the Preling has the referent in mind. Does it make a difference which of these ways of representing the referent we go with? We'll see later that it does have some implications. For now, for the sake of simplicity, we'll assume the localist position, which is the one that is assumed (though usually not explicitly) by most linguists and by many other language scientists.

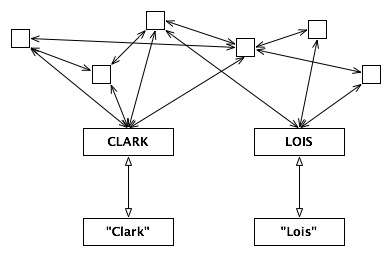

The picture so far, then, looks like that in the figure below. The large rectangles are meant to stand for some person's representation of two individuals (clark and lois) and the forms of the words that refer to them ("Clark" and "Lois"). The arrows connecting the pairs of rectangles represent the form-meaning relationship. The small squares above the boxes are supposed to suggest all the different features associated with Clark and Lois (their height, their personality, etc.) and the different responses that this person might have to Clark and Lois. Some of these are also connected to one another because they tend to be activated together. Note that these are supposed to be features that are shared across different individuals, so one of them (maybe for hair color) is associated with the rectangles for both people.

To use knowledge like this, Hearers would have to have a way to cause the form box to be activated when somebody says the word in their presence. This would then cause the meaning box to be activated and the boxes for the different features to be activated. Speakers would have to have a way of activating the different features associated with the person when thinking about or seeing that person. This would then cause the box for the meaning of the word to be activated, which would cause the box for the form of the word to be activated. There would then have to be be way for this to cause the Speaker to actually produce the word form. Note that I have left almost all of the details unspecified in these processes, and in fact much of what actually goes on when a person produces or understands a word like Lois remains controversial. Even the general structure of the knowledge shown in the figure would not be accepted by everybody.

One thing should be clear; however all of this works, it is very complex. So it would be hard to imagine how the relevant knowledge for a whole set of proper nouns could evolve in the Prelings. The alternative is that this knowledge is learned, that each member of the tribe must pick up the set of words from the other living members of the tribe. There is another good argument in favor of learning. The individuals that need to be referred to will change from generation to generation, so unless the chief of the tribe and other important members always look the same, there could be no words for these people. Of course simply saying that the knowledge is learned still leaves many questions unanswered. In particular it doesn't tell us where the names, or the idea of naming, came from in the first place. But we'll have to leave these sorts of questions unanswered so that we can move on.

Learning names

How might the learning of names take place? I've been arguing that names are a relatively simple, basic part of human language, so it shouldn't surprise us that proper nouns are among the first words that babies seem to learn. However, we have to be careful in assigning adult linguistic behavior to infants. When a baby utters "Mama" in the presence of its mother, does this mean that it is referring to its mother in the sense defined above? That is, does the baby want the Hearer to have its mother in mind? Almost certainly not. While it is probably true that Speakers reason about what is in or what could be in the minds of others, everyone who studies babies agrees that babies do not yet have this ability. In any case, for the moment, we won't bother with what it might mean to have a "theory of mind", as this is called. We'll just be concerned with the simpler problem of what it would mean for a baby to figure out how certain sounds or gestures are associated with particular individuals in the world.

Given the picture in the figure above, there would seem to be three parts to this process: learning the form, for example, learning what "Lois" sounds like and how to pronounce it; learning the meaning, for example, learning to identify what lois looks like and how she behaves; and connecting these two aspects of the word. In fact, if we start with the idea that language is about the relationship between forms and meanings, we could say the same thing for the learning of all linguistic patterns. Thinking of things this way — in terms of three separate learning processes — will often be useful, but is obviously an oversimplification because the processes can interact with each other in various ways. In particular there is the interesting possibility that people only learn the concept behind the meaning of a word (or other linguistic pattern) as they learn the word; that is, the existence of a single form for a range of different situations is what clues them into the existence of the concept in the first place. But to make sense out of this suggestion, we'll have to go far beyond names and proper nouns and look at the meanings of other types of words. In the next section we'll look at the general category of nouns.

2.2 |

Categories and common nouns |

The limitations of proper nouns

What would the disadvantages be of a language that contained only names, that is, words that applied to individual things (or situations)?

Names (in the form of proper nouns) buy our Prelings a lot. They can now call the attention of the members of their tribe to some of the important objects in their environment. But they can only do this for the objects that have names assigned to them. For each individual object, being named requires the following:

- The members of the tribe can all identify the object.

- The members of the tribe agree on the name for the object, that is, the form of the word.

- Each member remembers the name so that the form can be recalled when the Preling wants to refer to the individual and the name can be understood when another member of the tribe uses it.

Imagine the following situation. You have been out foraging around and have discovered a previously unknown person, apparently a member of another tribe, hiding near a large rock on the opposite side of the nearby river. Your tribe has an agreed-on name for the river but, though everyone is certainly familiar with the rock, no one has felt the need to refer to it before so it has no name. And because the new person is unknown to everyone in the tribe but you, that person can't have a name. You would desperately like to refer to these two individuals, the rock and the new person, but you can't. You need something more than simple names.

But names have another inadequacy. Recall one of the themes of this book, that language is constrained by the bodies and the cognitive capacities of language users. Now consider what it would be like to have a name, a separate proper noun, like Lois or Detroit, for every individual object you might ever refer to. Even if the members of your tribe could agree on the names, the limits of long-term memory would get in the way: how would you ever remember the millions of different names that you'd need?

It was convenient to begin the discussion of words and meaning with names, but for the reasons given above, maybe we shouldn't consider them to be the most basic kind of words.

Categories

The solution to the problems associated with names is provided by another basic human (and Preling) capacity, the capacity to categorize. People group objects in the world into categories on the basis of their similarities. Not only can we find individual apples, cats, and mountains in the world and distinguish individual apples, cats, and mountains from one another; we can categorize objects as being apples (and not pears or grapes), cats (and not dogs or goats), or mountains (and not valleys or boulders). An apple is an apple, that is, an instance of the category apple, because it shares properties with other apples. All apples have a characteristic shape, a characteristic taste and smell (though there are of course a number of variations), and a characteristic size (though there is again a range of precise possibilities), and all grow on a type of tree with typical properties of its own.

Our categories are to some extent natural; they correspond to relatively clean divisions in the world. Thus it's not just that we think apples are different from pears; they actually are. However, rather than thinking of categories as features of the world, we will be viewing them as cognitive entities, as concepts. This is because people clearly have the capacity to come up with categories for things that exist only in their imagination and because different cultures, and different people with the same culture, may categorize the same set of individuals differently. We'll see throughout this book how the similarities and differences between languages can give us insight into how human categorization works.

What good are categories? They permit people to respond in a similar fashion to many different objects once the objects can be categorized. Thus once you know an object is an instance of the category apple, you know that you can eat it or cut it up and put it in a pie. You don't have to learn separately for each individual apple what sorts of behaviors are possible.

Before we go on and relate categories to language, we need to remind ourselves

that we should be considering process as well as product.

Rather than think of categories as things in the mind, it will usually be more useful to think in terms of the process of categorization,![]() how a person figures out what category something belongs to so that they can then behave in an appropriate way for that thing (eat it, approach it, run from it, etc.).

As with individuals, we can think of categories as a localized or distributed in the mind of the categorizer.

For now, we'll assume that they are localized, that is, that there is a place in long-term memory dedicated to each category that the Preling or person knows.

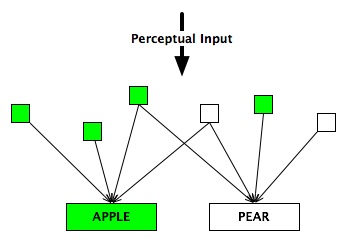

In such a system, categorization of an object of some sort would normally start with some perceptual input, that is,

something seen, heard, felt, smelled, and/or tasted by the categorizer.

This would then activate the places in memory dedicated to particular perceptual features.

that are associated with the object being perceived.

If these features overlap enough with the features in a category C and don't overlap more with the features of some other category, then the place in memory for category C is activated.

The figure below illustrates this process.

Some of the features (small squares) are activated by the perceptual input (activated features appear in green), and these are associated with two categories, apple and pear, but more strongly with apple, so it is activated.

how a person figures out what category something belongs to so that they can then behave in an appropriate way for that thing (eat it, approach it, run from it, etc.).

As with individuals, we can think of categories as a localized or distributed in the mind of the categorizer.

For now, we'll assume that they are localized, that is, that there is a place in long-term memory dedicated to each category that the Preling or person knows.

In such a system, categorization of an object of some sort would normally start with some perceptual input, that is,

something seen, heard, felt, smelled, and/or tasted by the categorizer.

This would then activate the places in memory dedicated to particular perceptual features.

that are associated with the object being perceived.

If these features overlap enough with the features in a category C and don't overlap more with the features of some other category, then the place in memory for category C is activated.

The figure below illustrates this process.

Some of the features (small squares) are activated by the perceptual input (activated features appear in green), and these are associated with two categories, apple and pear, but more strongly with apple, so it is activated.

The processing perspective also reminds us that categories like apple are not innate; they have to be learned. So a complete theory of categorization would also have to explain the learning process. But going into that now would lead us too far afield.

Common nouns

Now let's assume our Prelings have this powerful categorizing capacity. (There is good reason to believe that we're not the only animals that have it, by the way.) All we need to extend their primitive communcation system in a powerful way is to associate words with some of the categories. Human languages have such words; we will call them common nouns, words like apple, cat, and mountain. Now when a Preling wants to refer to an individual and doesn't have a name for it, there is still an out. If the Preling can categorize the individual and can find a common noun for that category in long-term memory, then they can use that noun to refer to the object. Of course the Hearer now has a new problem, that of figuring out which instance of the category the Speaker is talking about. If the Speaker says "rock", which rock is intended? For both Speaker and Hearer, there is clearly a lot of linguistic work to be done in using common nouns. But think how much more versatile the Prelings' communication system has become. With names they could only refer to the small set of individuals that had words assigned to them. Now they have the potential to refer to an infinite number of individuals, that is, all of the instances of all of the categories they have names for.

Probably because they are so frequent in our speech and because their function is not so complex, common nouns are among the first words that babies learn, at least in many languages. Babies' utterances early in their second year usually consist of single words, and many of these are common nouns such as juice or kitty. As with proper nouns, we have to be careful in interpreting children's utterances; when these words first appear, it is not necessarily the case that children are using them to refer to objects. They may simply have learned to respond with a particular word form when they are in the presence of particular things.

What categories are

When we want to find the meaning of a word, we often look it up in a dictionary. But remember that linguists are interested in describing the knowledge and behavior that ordinary native speakers of a language have. For linguists, why would dictionary definitions not work very well as accounts of word meaning?

What's the best way to describe human categories, including those that common nouns are associated with? Or alternately, what form do categories take in the mind? Or alternately, how do nouns mean? This question is one of the hardest and most contentious in the study of language, and there is no agreed-on answer. One possibility would be something like the definition in a dictionary. Here is Webster's definition for apple: "the fleshy usually rounded and red or yellow edible pome fruit of a tree (genus Malus) of the rose family". This seems to be on the right track, but it includes words like pome, which most native speakers (including me) don't know and the relationship between apples and roses, which, if people know it, doesn't seem central to their knowledge of apples. (In any case, a three-year-old, who may have no difficulty understanding and using the word apple, wouldn't normally know about this relationship.) Also the definition conveys nothing of what it feels like to bite into an apple, which for many people probably has something to do with what the word suggests to them.

Another problem with dictionary definitions as a model of what we know about words is that they are in the language that they are defining.

It is hard to imagine how a child its first words, a child who still knows almost nothing about the grammar of the language, would be learning meanings in the form of complex expressions in the language that is being learned.

Some linguists and philosophers of language have tried to come up with meanings for words that are somewhat like dictionary definitions, expressed that they are expressed in a different form, in a kind of "language of thought,"![]() which all children supposedly already somehow know.

But there have been problems with this view since it has been difficult to come up with definitions that hold in all cases.

There always seem to be exceptions.

Even for something as concrete and seemingly obvious as an apple, nothing seems to be absolutely necessary.

Does it have to have a peel and a cored?

No, a peeled or a cored apple is still an apple.

A particular texture?

It would strike us as strange, but something that is like an apple in every other way, but has the texture of butter, say, would still be an apple.

which all children supposedly already somehow know.

But there have been problems with this view since it has been difficult to come up with definitions that hold in all cases.

There always seem to be exceptions.

Even for something as concrete and seemingly obvious as an apple, nothing seems to be absolutely necessary.

Does it have to have a peel and a cored?

No, a peeled or a cored apple is still an apple.

A particular texture?

It would strike us as strange, but something that is like an apple in every other way, but has the texture of butter, say, would still be an apple.

One popular idea among linguists and psychologists is that a category

takes the form of a prototype,![]() a typical member of the category.

For example,

for me a prototypical apple is something like a Red Delicious: red, about 6 cm

across, and relatively sweet.

The prototype may include sensory features (e.g., what it looks and tastes like)

and features that have to do with function (what you do with it).

On this view, category membership is not an all-or-none matter; an individual

is a more or less good member of a category depending on how close it is to

the prototype.

A Granny Smith is an apple but not as "good" an apple as a

Red Delicious for me.

And a crabapple is even "worse."

a typical member of the category.

For example,

for me a prototypical apple is something like a Red Delicious: red, about 6 cm

across, and relatively sweet.

The prototype may include sensory features (e.g., what it looks and tastes like)

and features that have to do with function (what you do with it).

On this view, category membership is not an all-or-none matter; an individual

is a more or less good member of a category depending on how close it is to

the prototype.

A Granny Smith is an apple but not as "good" an apple as a

Red Delicious for me.

And a crabapple is even "worse."

The prototype idea makes sense because objects take more or less time for people to label with nouns or to identify when they hear the nouns. I would probably come up with the noun apple faster when I'm labeling a Red Delicious than when I'm labeling a Granny Smith. And I would think of or find a Red Delicious faster than a Granny Smith when I hear the word apple.

But there are still other proposals for what categories are. A quite radical one, but one that has been shown to agree with lots of data on categorization, is the exemplar-based theory (actually a whole family of related theories). In this approach there is no explicit representation of categories at all. Each category is just the set of all of the instances of that category that have been remembered (many imperfectly). What is an apple on this view? It is all of the individual apples that remain in the mind of a particular person. And hearing the word apple results in some combination of all of these being recalled all at once.

We will be meeting categories of one type or another in every section of this book. In fact to a large extent, the study of language is the study of linguistic categories. As we discuss these categories in more detail, it will sometimes be possible to ignore the details of how categories are represented and how categorization works, but at other times we'll have to consider how a prototype theory or an exemplar-based theory would differ.

Masses, things, and a lexicon

Before we go on, let's extend the range of things our Prelings can refer to. Say a Preling has noticed some smoke coming from across the river, a possible sign of another tribe, and wants to report this to the others. Smoke is not an object since it doesn't have well-defined boundaries, although, like objects, it does have characteristic and relatively constant properties, its color, its smell, the way it moves in the wind. We will refer to such things as masses. In human languages, masses tend to be referred to by words that are similar to the words used for referring to objects. Some English examples are fog, water, clay, wood, and soup. Like speakers of English and most other modern languages, our Prelings will use common nouns for masses as they do for objects. We will refer to the meta-category of objects and masses as things. Things are characterized by a set of relatively stable properties.

Our Prelings now have the potential for a very large set of words, as many as the categories that they group the things in their world into. Modern humans may know tens of thousands of nouns for the categories they need to refer to. While the Prelings are at this stage very far from having full-blown human language, they do have the beginnings, so it is time to change their name. They now have a lexicon, a mental dictionary of words, so we will call them Lexies.

2.3 |

Word senses and taxonomies |

Word senses

As cultures develop, they create or learn about new categories of things, for example, tools, and they then have the need to refer to these new things. Where might the words for the new categories come from?

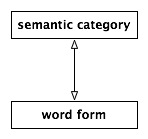

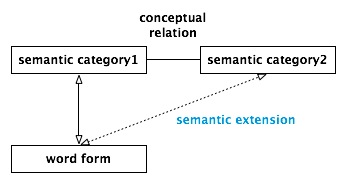

We have seen that words — common nouns — are associated with categories of things. I will refer to those categories that make up the meanings of words as semantic categories. As already noted, people also have plenty of categories that have no words associated with them. In fact which categories have labels varies from person to person and from language to language, as we will see soon. One way to summarize what we've discussed so far is shown in the figure below. So far the situation I've described looks like the following:

In the figure the word form is connected to the word's meaning, a semantic category, by an arrow that I will use to indicate a meaning relation. The arrow has two heads because a Speaker can get from a semantic category to a word form, and a Hearer can get from a word form to the word's meaning. You should already know that the figure does not correspond to everyone's view of what word meaning is because what I'm calling the "semantic category" could be distributed in various ways rather than localized as it appears here.

What happens when there is a new category that we need a word for? One possibility is to invent an entirely new word, but this apparently doesn't happen so often. More often the meaning of an existing word is extended to include the new category. When meaning is extended, this is done on the basis of some kind of relationship between the old meaning and the new. I will refer to this as a conceptual relation. The general situation involved in extending the meaning of a word, semantic extension, is shown in the figure below.

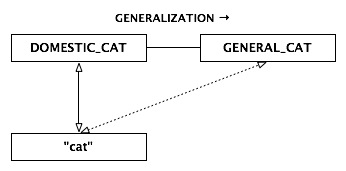

Let's see how semantic extension might work for our Lexies. Say they are familiar with domestic cats and have a word for them; for simplicity, let's say it's pronounced like the English word cat. Now they discover tigers and leopards. Each of these new categories gets its own noun, but in becoming familiar with these new animals, the Lexies see their similarities with domestic cats and develop a new category that encompasses all three categories of animals. How do they refer to this new category, that is, to the more general category of cats, what zoologists refer to as members of the family Felidae? (For simplicity, I'll call this category general-cat.) One possibility, which is the one used by many English speakers, is to refer to this category using the same word that is used for its most familiar sub-category, that is, cat. Note that the word cat now has two related meanings. I will refer to related meanings of a single word as word senses. For a word that has more than one sense, it is up to the Hearer to figure out when the word is used which of the senses is intended by the Speaker.

Here is another English example of a word with multiple senses. The noun chicken can refer both to a particular kind of bird (an object) and to a kind of meat made from this bird (a mass). Notice the two senses in the following sentences.

- There's a chicken walking around in the back yard.

- There's some chicken in the freezer.

The discussion so far might make it seem that language users, or entire language communities, extend the meanings of words consciously, but this rarely happens. Instead there seems to be a natural process by which the meanings of words change over time. As with other kinds of language change, the details of the process are not well understood. Somehow a change that starts with a small number of Speakers has to spread throughout the community and become conventional.

Generalization, specialization, and taxonomies

A baby uses the word truck for cars and buses as well as trucks. How would you describe this error? How is it like a semantic extension? He also uses the word train only for the toy train he plays with. How is this kind of error different from the first?

The extension of cat to include a new sense seems reasonable because the two senses are closely related. In this subsection, we'll examine this particular conceptual relation in more detail.

Every domestic cat is a member of the cat family (Felidae), that is, an instance of the category general-cat. Every tiger and every leopard is also an instance of this category. All of the properties that characterize the category general-cat, in particular, a characteristic body shape and way of moving, characterize domestic cats, tigers, and leopards. I will refer to the conceptual relation between the categories domestic-cat and general-cat as specialization-generalization. General-cat generalizes domestic-cat; domestic-cat specializes general-cat.

There is evidence from cognitive science that much of what we know about

objects is organized in terms of the specialization-generalization relation.

This is especially true for living things, for which we seem to represent

the categories in the world in

taxonomies![]() with multiple levels

for different degrees of generality.

Here is a possible portion of a taxonomy representing knowledge of animals.

There are three points to be mentioned about the figure, and about

conceptual taxonomies in general.

with multiple levels

for different degrees of generality.

Here is a possible portion of a taxonomy representing knowledge of animals.

There are three points to be mentioned about the figure, and about

conceptual taxonomies in general.

- As indicated by the small capitals, this is meant to represent a taxonomy of concepts, potential meanings of words, not a taxonomy of words.

- Such a taxonomy is a psychological entity; it represents the way some person might organize their knowledge about the world, not a scientific account of what is actually in the world. As you may know, zoologists would include several more levels in their scientific taxonomy for animals.

- As before, we need to be careful about taking the boxes too seriously since there are theories of categories that get by without anything so localized.

As we go higher in the figure, the categories become more general; there are fewer and fewer features that characterize their instances. Thus we can say a great deal about the characteristic sounds made by domestic cats, much less about the characteristic sounds made by members of the cat family, even less about the characteristic sounds made by mammals.

Here is another example, representing how someone might organize their knowledge about fruits.

Again there are fewer and fewer characteristic properties of the categories as we go higher in the taxonomy. Apples have a characteristic smell that resembles the smell of pears but is not characteristic of the smell of fruits in general.

Food, Fruit, Berry, etc., and using the inheritance mechanisms

that are built into the language itself to make use of the knowledge that is shared.

Or we can treat each category in the taxonomy as an object, an instance of a class like Concept and write procedures to implement inheritance bewteen these objects.

Most researchers have followed the second path, in part because it gives them control over how

inheritance works, how and when new categories are created and associated with the existing taxonomy.

But further consideration of these implementation issues is beyond the scope of this book.

What does all of this have to do with words? First, as we have seen from the example of cat, words may extend their meanings on the basis of the generalization relation. The noun cat came to mean not only domestic-cat, but also general-cat. The figure below illustrates this process.

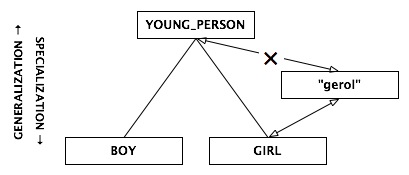

The opposite is also possible; a word may take on a sense that is more specific than its original sense. Consider the following example from the history of English. In Middle English the world gerol meant 'young person'. Over time the meaning of the word shifted to 'young female person', which is the sense it has in in its present form, girl. This is shown in the figure below, which illustrates the situation after the meaning had changed. The new sense was a specialization of the original sense. Notice that in this case, unlike what happened with cat in our first example, the original sense was lost after the word took on the new sense.

A similar process may occur when a word is borrowed from one language

into another; the sense of the word in the source language may be generalized

or specialized after the word enters the target language.

The usual

Tzeltal word

for 'person' is kirsiano (the exact pronunciation depending on the dialect), borrowed from the Spanish word cristiano

meaning 'Christian'.

For whatever reason, in the borrowing process the meaning was generalized

from 'Christian person' to (any) 'person'.

The Swahili![]() word safari means 'trip', but when this word was borrowed into

English from Swahili, it took on the special sense of a 'trip in search of game animals'.

In this case, the meaning was specialized when the word was borrowed.

word safari means 'trip', but when this word was borrowed into

English from Swahili, it took on the special sense of a 'trip in search of game animals'.

In this case, the meaning was specialized when the word was borrowed.

There are also many examples of generalization and specialization in the speech of young children. In this case we can think of the adult sense of the word as basic and the children's extension of this as a second sense, though it may not be clear that the child has learned the adult sense. Because these uses are seen as errors from the perspective of the adult model, they are referred to as over-generalization and under-generalization. An example of over-generalization is the use of dog to refer to other mammals roughly the size of dogs such as goats in addition to dogs. Examples of under-generalization are harder to observe because they require noticing that the child fails to use a word for a referent where an adult would use the word. An example would be the use of dog to refer only to a particular dog.

These errors made by children are interesting because they point up the possible similarity between the mechanism of language change and the mechanisms of language learning. What we see in the history of a language, the result of changes across an entire community, possibly over the course of multiple generations, resembles what we see in the development of a single child's linguistic system. We'll see more such examples in the book later on. The similarity implies that we might be able to understand language change as a process of learning taking place in the minds of many different language users, children and adults.

Finally, notice that there may be categories in a person's taxonomy that the person has no words for. Look at how the fruit taxonomy in the figure above corresponds to words for a particular English speaker (me).

While I have a category for things that are either apples or pears, that is, I recognize the similarities between apples and pears, I don't have a word for this category. Note that this does not imply that there is no word in the language for this category; botanists call the family that includes pears and apples Pomoideae. But I had never heard this word before I looked it up in order to mention it here, so it is (or was) not a part of my mental lexicon. Because I have words for all or most of the other categories in this taxonomy, we can consider the apple/pear category to constitute a lexical gap for me. We will see other examples of lexical gaps later in this chapter.

Problems

2.4 |

Metaphor and metonymy |

Metaphor

Consider the use of the word web for the World-Wide Web and the use of the word root to mean 'source' (as in the root of all evil). What is the basis for these semantic extensions? What do they have in common?

So far we've looked at how the meanings of words can be extended, both by adult speakers and by babies learning the language, in ways that make them more or less general. In this section we'll consider two other general kinds of conceptual relations that permit word meanings to be extended: similarity and various kinds of close association.

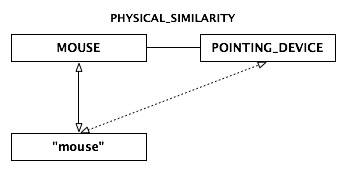

First consider the situation that arose when computers were first outfitted with pointing devices to be manipulated in one hand by moving them across a pad and pushing one of their buttons. The noun that came to be used for these devices, mouse, was based on the resemblance of the devices to the animal: the general size and shape and the tail-like cable. Thus the meaning of the word mouse was extended on the basis of the physical similarity between one category (the animal) and another (the pointing device). Extension of a word's meaning on the basis of similarity is known as metaphoric extension. This figure illustrates the process.

Here is another computer-related example. When computer software started providing users with sets of choices that they could select from, the word that emerged for these lists was menu. The metaphoric extension was based on the similarity between a restaurant menu, a list of food and drink choices, and the list of choices that the computer user was to select from.

One frequent use of metaphor is the application of a word referring to an object category to a more abstract semantic category, something not physical at all. Consider the structure of taxonomies as in this example from the last section. If we turn the figure illustrating the taxonomy over, it resembles a tree, with the most general category as the root and the most specific categories the leaves. This is in fact how cognitive scientists refer to structures like this; tree is applied to the whole structure, root is applied to the point where all of the branches begin, and leaf is applied to the point beyond which there are no more branches. Note that a taxonomy is not a physical thing at all, so with metaphoric extension we have now taken common nouns such as tree and leaf outside of the realm of the physical entirely.

This example also illustrates how metaphor![]() often operates on two entire domains, each with its own elements and internal structure.

The source domain is the one that is being used to understand

the (usually more complex) target domain.

In this example, the source domain is tree, the target

domain taxonomy.

The metaphor is based on multiple similarities between the domains: correspondences (or mappings) between the elements (leaves and specific concepts, for example) and the relations between the elements (branches join the root to the leaves; generalization links join the most general concept to the more specific ones).

often operates on two entire domains, each with its own elements and internal structure.

The source domain is the one that is being used to understand

the (usually more complex) target domain.

In this example, the source domain is tree, the target

domain taxonomy.

The metaphor is based on multiple similarities between the domains: correspondences (or mappings) between the elements (leaves and specific concepts, for example) and the relations between the elements (branches join the root to the leaves; generalization links join the most general concept to the more specific ones).

Metonymy

The word for 'language' may be related to other, less abstract words,

for example, the word for 'tongue' (as in Spanish),

the word for 'mouth' (as in Oromo![]() ),

the word for 'voice' (as in Tzeltal).

Assuming that the 'language' sense is an extension of the more basic

sense in each case, what's the basis of this extension?

),

the word for 'voice' (as in Tzeltal).

Assuming that the 'language' sense is an extension of the more basic

sense in each case, what's the basis of this extension?

A somewhat more complicated possibility for extending a word meaning is

based on a quite different conceptual relation, not similarity between

the instances of the two categories but a strong association between

them.

This is referred to as

metonymic extension.![]() Consider the association between an organization (an abstract concept), such as a

sports team or a government, and its base location.

While we can refer to the organization directly using its name,

we often find it convenient to use the name of the location

to refer to the organization.

Consider the association between an organization (an abstract concept), such as a

sports team or a government, and its base location.

While we can refer to the organization directly using its name,

we often find it convenient to use the name of the location

to refer to the organization.

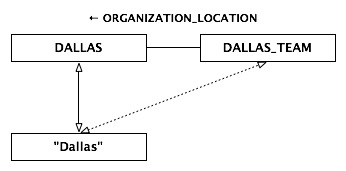

- Dallas won yesterday's game.

- No one is sure what Moscow's response will be.

This figure illustrates the first example of metonymy.

Another conceptual relation that permits metonymy is that between a document and the content of the document. Thus the word book refers to a physical object: a collection of sheets with printing or pictures on them that is bound together. But we can also use the word to refer to the informational content of the physical book. Compare the uses of the word in these two sentences.

- This book is almost too heavy to lift.

- I don't understand this book at all.

In the first example, the speaker is clearly referring to the physical object, in the second example to the information contained in the physical object. In a case like this, metonymic extension allows a noun referring to a physical object to refer to something more abstract.

Metonymy may also be used in situations where an alternative to an existing noun is called for, perhaps as a very informal or insulting term. Examples are the use of wheels to mean 'car', brain to mean 'intelligent person', and asshole to mean 'person' in an insulting context. In these examples the relevant conceptual relation is between a whole and a part. (There is much more going on than just this, especially in the last example, because the choice of the particular part is obviously also relevant!)

Metonymy may also come into play "on the fly", when a speaker is using language

creatively.

Here's an example from

Fauconnier (1985).![]() One waitress in a restaurant is speaking to another.

One waitress in a restaurant is speaking to another.

- The omelet left without paying.

Of course the speaker doesn't mean that some cooked eggs left the restaurant; she is referring to a customer. The conceptual relation that is the basis for the metonymic extension in this case is the relation between a customer and the customer's order. Note that omelet would only be expected to get this interpretation in the appropriate context; that same person would not normally be called the omelet.

Finally we see apparent examples of metonymy in the speech of young children. Andrés, who was learning both English and Spanish, used the Spanish word luna ('moon' in adult Spanish) during his second year to refer not only to the moon and crescent shapes but also to the pens or pencils used to draw crescent shapes. It appears that he has extended the word on the basis of the relation between an image and the instrument used to produce the image. But, as always, we must be careful in interpreting children's utterances. Most of Andrés' utterances during this period consisted of a single word. When he said "luna" apparently referring to a pen, did he really mean something more like "use this to draw a crescent"? We have no simple way of knowing.

Problems

2.5 |

Deixis and person |

Utterance contexts

Consider the sentence I love you. What changes in the interpretation of the words I and you when different speakers say this to different hearers?

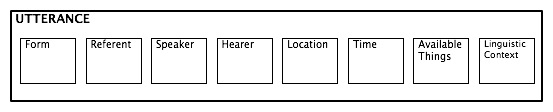

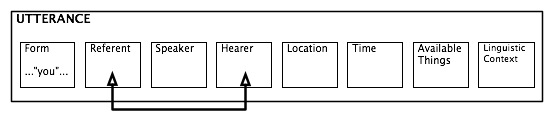

Each time a Speaker refers, there is a word (or more) that is uttered, that is, a form, and there is a referent, the thing that is being referred to. (Of course the referent may be something imaginary, but we can still talk about it existing in the mind of the Speaker.) But for each reference, there are always in addition several other things: the Speaker, one or more Hearers, the time and place of the reference, a set of things that the Speaker and the Hearer are currently aware of, and possibly some other language that has just been produced by the Speaker, the Hearer, or somebody else. A particular instance of language is an utterance. An utterance needs to be distinguished from a particular word, phrase, or sentence because an utterance has an utterance context, a particular Speaker, Hearer, time, place, available things, and recent language, in addition to its own linguistic form. I'll sometimes refer to the Speaker and Hearer as utterance participants. For example, we can put the English words I, like, and it together to make the English sentence I like it, but this sentence is a different utterance each time it is uttered.

Each utterance has its own context, and, as we will see below, for each context the sentence has a different meaning. That is, meaning always changes from one utterance context to another. The figure below is one way of representing the elements of an utterance context. Each of the elements is a role in the context, a kind of slot that gets filled by something in each different situation. For example, the Speaker role is filled by a particular person, and the Location role is filled by a particular place. We will meet the concept of role again later in this book; in fact it is one of the most fundamental notions in cognitive science.

Deixis

How does the notion of utterance context help us understand how words like I and you refer?

Now we'll examine how our Lexies can use the idea of utterance context to come up with a new way to refer to some of things around them. Each person in the tribe has a name, and when referring to members of the tribe, a Speaker can use the name of the referent (a proper noun such as Philip). Proper nouns have an unusual property; unless there is more than one individual with the same name, proper nouns always refer to the same individual in the world, no matter when, where, and by whom they are uttered. (Note that this is not true of common nouns; we can use the noun apple at different times to refer to any number of different individual apples in the world.)

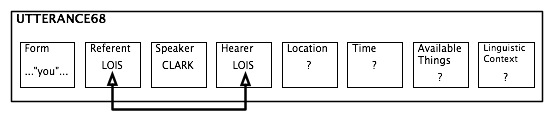

Now consider an approach to reference that is in a sense the opposite of that taken with proper nouns, which are completely independent of the utterance context, one in which the meaning depends completely on the utterance context. Say Clark is speaking to Lois and wants to refer to Lois. He could use her name, a proper noun. Or he could use a word which refers to the Hearer, whoever that might be. This is how the English word you works. Without knowing the utterance context, or at least knowing who the Hearer is, we have no idea what the referent of you is. The figure below illustrates the meaning of you. The referent of a you utterance is joined by the meaning arrow to the role of Hearer rather than to a particular individual (as for proper nouns) or a category (as for common nouns).

For each utterance of you, the word gets its interpretation from the utterance context, that is, who it is that fills the role of Hearer. So in our example, with Clark as the Speaker and Lois as the Hearer, the situation is as shown in the figure below. There are question marks in the Location and Time roles because we don't know what these are, and the number at the end of "utterance" is meant to indicate that this a particular utterance, not the general prototype for utterances shown in the previous two figures.

You is an example of a

deictic![]() expression, an expression

that gets its meaning directly from the utterance context, that

makes reference to one or more of the roles in the utterance

context: the Speaker, the Hearer, the location, or the time.

The noun form of the word is deixis.

expression, an expression

that gets its meaning directly from the utterance context, that

makes reference to one or more of the roles in the utterance

context: the Speaker, the Hearer, the location, or the time.

The noun form of the word is deixis.

You may already have figured out where we're going next.

Just as we have an English word to refer to whoever the Hearer is, we have

a word to refer to whoever the Speaker is: I (or me).

I gets its meaning from the utterance context just as you

does.

You and I are examples of

personal

pronouns,![]() words which refer directly to participants in the utterance context.

All languages apparently have personal pronouns, a quite striking

universal property,

though languages differ greatly in the details, as we will see

later on.

words which refer directly to participants in the utterance context.

All languages apparently have personal pronouns, a quite striking

universal property,

though languages differ greatly in the details, as we will see

later on.

Person

What information is conveyed by the word her in the sentence I love her? Does (or could) the meaning of the word change with the utterance context as it does for I?

The personal pronouns I and you are alike in a number of ways;

they differ with respect to their

person,![]() that is, which utterance

participant they refer to.

Conventionally we call reference to the Speaker first person and reference to the Hearer

second person.

Note that reference that

includes the Speaker as well as other people

is considered first person; thus we is a first person pronoun.

The commonality between I and we is not something that is reflected in form in English, but we should not be surprised to find it elsewhere.

In Japanese, there are many words for I, but each of these words has a corresponding form ending in -tachi that means 'we': for example,

watashi, boku, ore 'I'; watashitachi, bokutachi, oretachi 'we'.

that is, which utterance

participant they refer to.

Conventionally we call reference to the Speaker first person and reference to the Hearer

second person.

Note that reference that

includes the Speaker as well as other people

is considered first person; thus we is a first person pronoun.

The commonality between I and we is not something that is reflected in form in English, but we should not be surprised to find it elsewhere.

In Japanese, there are many words for I, but each of these words has a corresponding form ending in -tachi that means 'we': for example,

watashi, boku, ore 'I'; watashitachi, bokutachi, oretachi 'we'.

What about reference to things (or abstractions) that are (or include) neither the Speaker nor the Hearer? Here things get a little more complicated. Clearly any reference which is not first person or second person belongs to this category, which is known as third person. So in the following sentence, the expressions in bold are third person.

- Clark told his sister about the movie.

This sentence makes reference to three different things, and none of these either is or includes the Speaker or Hearer. None of these references seems to be deictic either since their meanings do not seem to depend on the utterance context, on who says the sentence to whom and on when and where it is said. (This is not quite true — the interpretation of the movie in this sentence does depend on the utterance context — but we will not worry about this aspect of deixis.)

Just as we have first and second person pronouns which say nothing more about the referent than that it is (or includes) the Speaker or Hearer, we have third person pronouns which say little more about the referent than that it does not include the Speaker or Hearer. Third person pronouns in English include she, he, it, and that. Notice that these pronouns do provide a little more information about the referent than that it is third person (neither Speaker nor Hearer). They also tell us something about the gender of the referent. He refers to something that is not the Speaker or Hearer and is perceived as male. (Note that the referent doesn't have to be male in a biological sense. In informal English we often use he in informal English to refer to animals without actually checking first to make sure we have their gender right. Another way to look at this usage is to think of the male pronouns as the default, the form we use for animals when we don't know the gender.) Similarly, she refers to something that is not the Speaker or Hearer and is perceived as female, and it and that refer to something which is perceived as non-human.

Note how third person pronouns act as shortcuts; in this sense they are Speaker-oriented. To refer to something, a Speaker can just say "it" and not bother coming up with the name of the thing or a common noun for its category. Of course the burden is then on the Hearer to figure out which non-human thing the Speaker is referring to. This implies two things about language learning. First, people have to learn how to interpret such pronouns. This is not trivial, and it has proven to be one of the most difficult language behaviors to get computers to do. Second, people have to learn in what situations it is appropriate to use such pronouns. Consider the following sentence uttered at the beginning of a conversation.

- Did you find it?

This sentence sounds silly unless the Speaker somehow knows that whatever it refers to is on the Hearer's mind and that nothing else the Hearer might have been looking for is.

Let's summarize what we've given our Lexies in this section. Personal pronouns don't actually allow them to refer to any new things in the world that they couldn't already refer to; they already had proper nouns or common nouns for this purpose. Instead personal pronouns give them a new way to refer, using the roles of the utterance context directly. As we have seen, utterance contexts have more than just a Speaker and a Hearer, and we can expect languages to have deictic words that refer to the other roles as well. Words such as here and now do exactly that.

Learning deixis

If young children learning English treat the word you like a proper noun instead of a person pronoun, what kinds of mistakes will they make?

As we have seen, young children must learn to refer using words that point directly to individuals (proper nouns), words that point to categories of things (common nouns), and words that point to deictic roles. Deixis seems to be the last of these to emerge. Early on children often treat first and second person pronouns as though they were proper nouns. So when the Speaker uses the word you to refer to the Hearer (the child), the child may also use the word you to refer to herself, who is now the Speaker. Perhaps deixis is hard for a child because it requires switching perspective. The child can't simply imitate the adult usage because the roles of Speaker and Hearer switch when this happens, and deictic words like I and you change their referents. In some sense the child has to understand a word like you from the perspective of the Speaker, realizing that that person then fills the you role when she becomes the Speaker.

Third person pronouns are difficult for children in a related way. As we have seen, their appropriate use depends on the ability to know whether the Hearer can interpret them, that is, in some sense on the ability to put oneself in the position of the Hearer. Because this is apparently difficult for children, they often produce sentences like the following in a situation where the Hearer would have no way of figuring out who he is.

- He hit me.

2.6 |

Lexical differences among languages |

Some reasons languages differ lexically

So far we have endowed our Lexies with an amazing capacity, one that to date has only been found among human beings. Over the generations, they can now invent a very large store of labels for individuals and categories of things in the world (even categories of things not in the world). And, equally important, they can pass on this store of labels to their children.

Now let's imagine various tribes of Lexies in different parts of the world with no contact with each other. Each tribe will experience a different environment, containing its own potentially unique set of animals and plants and its own climate and geology. Each tribe will invent words for the things in its environment that matter to it, and we will naturally expect to find words for different things in each tribe. Modern languages also differ from each other in this way. Amharic has a word for hippopotamus because hippopotamuses are found in Ethiopia, but Inuktitut does not because hippopotamuses are not found (normally) in northern Canada.

We can also expect the cultures of the different tribes of Lexies to differ. This will result in several differences in their store of words. First, certain naturally occurring things will become more important. A tribe that makes pots out of clay will want a word for clay; another tribe may not bother. Second, as culture develops, there will be more and more cultural artifacts, that is, objects produced by the members of the culture. Naturally the tribe will want words for these as well, and if they are not producing them, they will not have such words. Finally, culture results in abstractions, concepts that do not represent (physical) things in the world at all: political units, social relationships, rituals, laws, and unseen forces. These will vary a great deal in their details from tribe to tribe, and we can expect these differences to be reflected in the words that each tribe comes up with.

Modern languages also differ from each other in these ways. Amharic has the word agelgil meaning a leather-covered basket that Ethiopians used traditionally to carry prepared food when they traveled. Other languages don't have a word for this concept. English now has the word nerd to refer to a particular kind of person who is fascinated with technology and lacking in social skills. This is a relatively new concept, specific to certain cultures, and there is probably no word for it in most languages.

Differences within and among languages

Languages such as English, Spanish, Mandarin Chinese, and Japanese have many specialized terms for computers and their use, whereas many other languages, such as Tzeltal and Inuktitut, do not. Does this represent some kind of fundamental limitation of these languages?

Finally we can also expect the store of words to vary among the individuals within each tribe. As culture progresses, experts emerge, people who specialize in agriculture or pottery or music or religion. Each of these groups will invent words that are not known to everyone in the tribe. Modern languages also have this property. A carpenter knows what a hasp is; I have no idea. I know what a morpheme is because I'm a linguist, but I don't expect most English speakers to know this.

This brings up an important distinction, that between the words that a language has and the words that an individual speaker of the language knows. Because some speakers of languages such as Mandarin Chinese, English, Spanish, and Japanese have traveled all over the world and studied the physical environments as well as the cultures they have found, these languages have words for concepts such as hippopotamus and polygamy, concepts that are not part of the everyday life of speakers of these languages. Thus it is almost certainly true that Mandarin Chinese, English, Spanish, and Japanese have more words than Amharic, Tzeltal, Lingala, and Inuktitut. But this fact is of little interest to linguists and other language scientists, who, if you remember, are concerned with what individual people know about their language (and sometimes other languages) and how they use this knowledge. There is no evidence that individual speakers of English or Japanese know any more words than individual speakers of Amharic or Tzeltal.

Furthermore, if a language is lacking a word for a particular concept, it is a simple matter for the speakers of the language to add a new word when they become familiar with the concept. One way for this to happen is through semantic extension of an existing word; we saw this earlier with mouse in English. Another way is to create a new word out of combinations of old words or pieces of old words; we will see how this works in in Chapter 5 and Chapter 8. A third, very common, way is to simply borrow the word from another language. Thus English speakers borrowed the word algebra from Arabic; Japanese speakers borrowed their word for 'bread', pan, from Portuguese; Amharic speakers borrowed their word for 'automobile', mekina, from Italian; and Lingala speakers borrowed their word for 'chair', kiti, from Swahili.

Lexical domains: personal pronouns

What are the differences between the personal pronouns you and you guys? (There are at least two differences.)

More interesting than isolated differences in the words that are available in different languages is how the concepts within a particular domain are conveyed in different languages. We'll consider two examples here, personal pronouns and nouns for kinship relations; we'll look at others later on when we discuss words for relations.

A complete set of personal pronouns in my dialect of English includes the following: I, me, you, she, her, he, him, it, we, us, you guys, they, them. Note that I'm writing you guys as two words, but in most important ways it behaves like one word. For our present purposes, we can ignore the following group: me, her, him, us, them; we're not really ready to discuss how they differ from the others. Among the ones that are left, let's consider how they differ from each other. We have already seen how they differ with respect to person: I and we are first person; you and you guys are second person; she, he, it, and they are third person. We can view person as a dimension, a kind of scale along which concepts can vary. Each concept that varies along the dimension has a value for that dimension. The person dimension has only three possible values, first, second, and third, and each personal pronoun has one of these values.

Person is not just a conceptual dimension; it is a semantic dimension because the different values are reflected in different linguistic forms. That is, like words, semantic dimensions have both form and meaning. When we speak of "person", we may be talking about form, for example, the difference between the word forms I and you, about meaning, for example, the difference between Speaker and Hearer, or about the association between form and meaning.

But person alone is not enough to account for all of the differences among the pronouns. It does not distinguish I from we, for example. These two words differ on another semantic dimension, number. I is singular: it refers to an individual. We is plural: it refers to more than one individual. What values are possible on the number dimension? Of course languages have words for all of the different numbers, but within the personal pronouns, there seem to be only the following possibilities: singular, dual (two individuals), trial (three individuals), and plural (unspecified multiple individuals). Of these trial is very rare, and, among our set of nine languages, dual is used only in Inuktitut. Thus Inuktitut has three first person pronouns, uvanga 'I', uvaguk 'we (two people)', uvagut 'we (more than two people)'.

Given the two dimensions of person and number, we can divide up the English personal pronouns as shown in the table below. The third person pronouns fall into the singular group of three, she, he, and it, and the single plural pronoun they. The second person is more complicated. In relatively formal speech and writing, we use you for both singular and plural, but informally, at least in my dialect, we may also use you guys for the plural. (Note that other English dialects have other second person plural pronouns, you all/y'all, yunz, etc.) Thus we need to include both you and you guys in the plural column.

|

|

sing. | plur. |

|---|---|---|

| 1 pers. | I | we |

| 2 pers. | you | you, you guys |

| 3 pers. | she, he, it | they |

Clearly we need more dimensions to distinguish the words since two of the cells in our table contain more than one word. Among the third person singular pronouns, the remaining difference has to do with gender, whether the referent is being viewed as male, female, or neither. Instead of male and female, I will use the conventional linguistic terms masculine and feminine to emphasize that we are dealing with linguistic categories rather than biological categories in the world, and for the third value I will use neuter. Thus there are three possible values on the gender dimension for English, and three seems to be all that is needed for other languages, though some languages have a dimension similar to gender that has many more values.

That leaves the distinction between you and you guys in the plural. As we have already seen, this is related to formality, another semantic dimension and a very complicated one. I will have little to say about it here, except that it is related to the larger context (not just the utterance context) and to the relationship between the Speaker and Hearer. For example, language is likely to be relatively formal in the context of a public speech or when people talk to their employers. For now, let's assume that the formality dimension has only two values, informal and formal. The table below shows the breakdown of the English personal pronouns along the four dimensions of person, number, gender, and formality.

|

|

sing. | plur. | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1prs. | I | we | ||||||

| 2prs. | you |

|

||||||

| 3prs. |

|

they |